internationalizing and localizing your app, part 3: technical challenges

Internationalizing and Localizing Your App, Part 3: Technical Challenges§

In part three of this four part tutorial, learn about how to solve for the various considerations and nuances of language. This includes pluralization, accessibility, formatting dates and numbers, and more!

Check out part 2 of this series here.

Let Unicode lead the way§

In 2003, the Unicode Consortium released the first major version of the project known as the Common Locale Data Repository, shortened to CLDR, a massive XML dataset that houses many internationalization, localization, and translation specific data and rules. Ever since, the repository has grown and now reaches major version 39 at the time of writing. Some of the things encoded by the CLDR include:

-

Translations for language names

-

Translations for territory and country names

-

Translations for currency names, including singular/plural modifications

-

Translations for weekday, month, era, period of day, in full and abbreviated forms

-

Translations for time zones and example cities (or similar) for time zones

-

Translations for calendar fields

-

Patterns for formatting / parsing dates or times of day

-

Exemplar sets of characters used for writing the language

-

Patterns for formatting / parsing numbers

-

Rules for language-adapted singular, plural, and ordinal phrasing

-

Rules for language-adapted collation

-

Rules for formatting numbers in traditional numeral systems (like Roman numerals, Armenian numerals, etc.)

-

Rules for spelling out numbers as words

-

Rules for transliteration between scripts. Much of it is based on BGN/PCGN romanization

Leveraging this data can be as simple as downloading and parsing the XML, however, it’s often useful to lean on standardized, CLDR-backed libraries or APIs, such as the Intl APIs provided in most modern browsers and recent versions of Node (or some similar language / platform specific implementation of CLDR data).

Another consideration thought out by the Unicode Consortium is how to handle properly truncating or splitting words by using grapheme clusters, so as to determine the proper place in which a group of characters can be split while still preserving meaningful chunks of text. This alone could be an entire article, but it’s safe to say that String.slice(...) will not suffice if you need to manually manipulate your strings for whatever reason.

Locale specific formatting§

Of course, every locale has a unique way of handling the formatting of certain data. The most common example of this, and one which you’ve most likely encountered before, is currency. Each currency uses some specific symbol, such a $ or ₺. On top of that, it is common for currencies to also be formatted differently across regions based on the way in which each region represents numbers. For example, let's use the Intl.NumberFormat API to check a few numbers:

const number = 123456.789;

console.log(new Intl.NumberFormat("en-US", { style: "currency", currency: "USD" }).format(number));

// expected output: "$123,456.79"

// Notice the difference between , and . in the USD example

console.log(new Intl.NumberFormat("de-DE", { style: "currency", currency: "EUR" }).format(number));

// expected output: "123.456,79 €"

// the Japanese yen doesn't use a minor unit

console.log(new Intl.NumberFormat("ja-JP", { style: "currency", currency: "JPY" }).format(number));

// expected output: "¥123,457"

Of course, this applies to more than just currencies, but also to things like percentages, which are used all over OkCupid to denote the match percentage between two users. Here’s an example of how percentages are localized:

// Percentages operate between 0.0 and 1.0 in this API.

const number = 0.95;

console.log(new Intl.NumberFormat("en-US", { style: "percentage" }).format(number));

// expected output: "95%"

console.log(new Intl.NumberFormat("de", { style: "percentage" }).format(number));

// expected output: "95 %"

console.log(new Intl.NumberFormat("tr", { style: "percentage" }).format(number));

// expected output: "%95"

These APIs are incredible powerful and are part of most recent browsers (and natively in recent Node versions). They also provide ways to format numbers for things such as using different digit sets for some locales, localizing distances / speeds / metric measurements, and much more.

There are other things that we should also make certain to properly localize within our applications, such as dates, times, relative times, and even lists:

const date = new Date();

console.log(new Intl.DateTimeFormat("en-US").format(date));

// expected output: "4/19/2021"

console.log(new Intl.DateTimeFormat("tr").format(date));

// expected output: "19.04.2021"

console.log(new Intl.RelativeTimeFormat("en-US", { style: "long" }).format(-1, "day"));

// expected output: "1 day ago"

console.log(new Intl.RelativeTimeFormat("tr", { style: "long" }).format(-1, "day"));

// expected output: "dün"

const toppings = ["Cheese", "Pepperoni", "Veggies"];

console.log(new Intl.ListFormat("en-US", { style: "long", type: "conjunction" }).format(toppings));

// expected output: "Cheese, Pepperoni, and Veggies"

console.log(new Intl.ListFormat("de", { style: "long", type: "disjunction" }).format(toppings));

// expected output: "Cheese, Pepperoni oder Veggies"

It’s also worth mentioning that another thing that is often overlooked when localizing values like this is that the notion of “sorting alphabetically” will change given the language in use, as the glyphs in use in a given language will change and a simple .sort(...) will certainly not take locale into consideration by default. Luckily, the CLDR has us covered once again by providing rules for collating so that sorting may be localized as well. The Intl APIs also expose a Collator for this purpose.

Of course, the best source of truth for all of this information will always be the most recent version of the Common Locale Data Repository, and leveraging any API implementation of this datasource (such as the Intl APIs) is a great way to ensure your providing the correct data for a given locale.

Accessibility§

Perhaps one of the more important topics in software, particularly in the past few years, accessibility is a core feature of a lot of applications. Mozilla defines accessibility as:

Accessibility is the practice of making your websites usable by as many people as possible. We traditionally think of this as being about people with disabilities, but the practice of making sites accessible also benefits other groups such as those using mobile devices, or those with slow network connections.

If we take this definition at its face, then I’d posit that there is an extension to be made here, in that internationalization should be considered a tenet of accessibility. We are working to open up our software to entire groups of people who previously had limited or no meaningful access to it, and make it as accessible and relevant to these people.

For developers, this means we should also ensure that all of the work we do to ensure our apps are accessible ought to tie in directly with the work we do to internationalize our apps. If we are providing meaning accessibility labels via alt and aria-* attributes and the like, we should also make sure they are properly translated as well, something that's very easy to overlook.

Also, we ought to focus on the parsing of our documents by accessibility tools and the gestures our users can take, making sure that these are properly localized as well. It’s important to make sure our documents are properly tagged (for example, using the HTML lang attribute) so that other software like accessibility aids can be made aware that the document in question is in a certain language. As for gestures, imagine being accustomed to a right-to-left language like Arabic or Hebrew: how would one properly localize a feature like "swiping left" and "swiping right"? Naturally, these are features born from a western experience and it's interesting to consider how it would hold up in a layout and script for which they were not originally designed.

API Design, Redesign?§

Where should localization happen?

When working on localizable content in your application, content negotiation and particularly the role of the accept-languages header will be paramount to getting a read on what locales a user will be expecting to receive when they make a request to your web server or service. Although this is a specific feature of HTTP content negotiation, the concept of having a uniform way in which a user’s locale code(s) can be propagated throughout a system can be applied abstractly and across various protocols. There are of course other ways of denoting a language preference, perhaps most common otherwise would be the usage of a URL query parameter, such as www.somesite.com/home?lang=en. There are of course trade-offs between the more implicit header-based approach and the more explicit parameter based approach, and should be weighed given other factors in your application such as request / response caching mechanisms.

Perhaps a pitfall common for many APIs that were designed without internationalization in mind, it is crucially important to make sure each of the data points (or at least some representation of them) has a way for it to be uniquely identified. Working with strings directly is seldom better than individual IDs when it comes to internationalizing a service or API, as it allows for both client and server code to remove a dependency on variable data. For example, let’s abstractly sketch out a contrived set of requests where we want to get some data that can then be used in subsequent tangential requests:

GET "api/menu/pizza_toppings" --> ["Cheese", "Pepperoni", "Veggie"]

POST "api/my_pizza/add_topping" --> ("Pepperoni") --> { success: true }

Consider that if we want to support the translation of these data points returned by /pizza_toppings so that our users can see a localized version of the text, the endpoint at /add_topping is probably not equipped to understand values other than ["Cheese", "Pepperoni", "Veggie"], and so if we translate those values into their equivalent in another language, our client will be sending bogus requests. Contrast that with something like the following:

GET "api/menu/pizza_toppings" --> [

{ id: 1220, name: "Cheese" },

{ id: 1234, name: "Pepperoni" },

{ id: 1002, name: "Veggie"}

]

POST "api/my_pizza/add_topping" --> (1234) --> { success: true }

By structuring the input and output of our APIs and services in a more normalized format, we can now trivially translate the name fields of the /pizza_toppings payload and not need to worry about breaking our software by adding support for other languages. This may seem obvious to some, but I'd highlight the fact that in high-velocity situations it's easy to overlook something that you're not currently designing for (hindsight is 20:20), and so it's understandable that for software that was not originally expected to support features like localization, an engineer could very easily have opted for the former example for the sake of it's simplicity.

Finally, it’s worth taking a moment to analyze the architecture of your current application and question whether or not it will be necessary (and subsequently, possible) to supporting various languages and regions. If you have a service which will need to adapt given linguistic, cultural, or legal requirements of a given locale, how does this variability fit into the current architecture of your APIs and services. It’s possible that there may need to be services dedicated specifically for the task of determining mappings of features given a locale or region.

Styles, theming, assets§

Like I had mentioned earlier, capitalization is a very important syntactical feature of some languages. For that reason, I feel it is best to avoid using code like CSS text-transforms or Javascript's String.toUpperCase to perform explicit changes to the case of a message that will be displayed to a user. You can almost be guaranteed that this will inadvertently corrupt the translation of a message at some point. Let's look at an example here, where for example, we want to capitalize the name of a user and their location:

const user = "Nick";

const city = "Cincinnatti";

// EN-US

console.log(user.toLocaleUpperCase('en-US')); // "NICK"

console.log(city.toLocaleUpperCase('en-US')); // "CINCINNATTI"

// TR

console.log(user.toLocaleUpperCase('tr')); // "NİCK"

console.log(city.toLocaleUpperCase('tr')); // "CİNCİNNATTİ"

Well, now we’ve just actually mistranslated two messages in Turkish, as my name is not NİCK and the name of the city is not CİNCİNATTİ, regardless of the fact that the glyph i should become İ when uppercased in Turkish.

Another important piece to keep in mind when it comes to the styling of our software is to ensure that our components can easily scale and grow given their content. Consider that a phrase that is only just a few words or letter in English can easily double or triple in length when translated in to other languages (or vice versa). Part of this certainly a design problem, but it is also our responsibility to make sure we’ve accounted to variable length strings in our designs so that translation does not cause our components to clip or break in any way.

Along with designing for different expected lengths of our content, we should also keep in mind that our components should be built in a way in which they are able to be used in a variety of languages’ scripts, regardless of the particular direction of the selected script. Take this contrived CSS as an example:

/* Left and right values will always be the same */

.bad-page-title {

margin: 16px 32px 16px 4px;

}

.bad-page-subtitle {

margin-left: 16px;

margin-right: 24px;

}

/* document.dir changes will automatically lay this out properly */

.good-page-title {

margin-inline-start: 16px;

}

.good-page-subtitle {

margin-block-end: 32px;

}

Carefully using start and end values as opposed to left and right values will allow our stylesheets to scale effortlessly across languages with left-to-right scripts and right-to-left scripts! Neat!

Perhaps another area to really make your localization work stand out would be to use custom theming for different locales. Like I mentioned earlier, colors and symbolism are all subject to the culture and language they’re presented in, so using something like a ThemeProvider from styled components to manage a theme based on the application's active locale could be a very interesting way to make your product feel more natural and stand out more in different regions and languages. For example, our color for error messages can be red for western locales where the color is often associated with errors, but not for some East Asian locales where that color is not often associated with errors. That's a small example, but the possibilities for locale specific theming are practically endless, though.

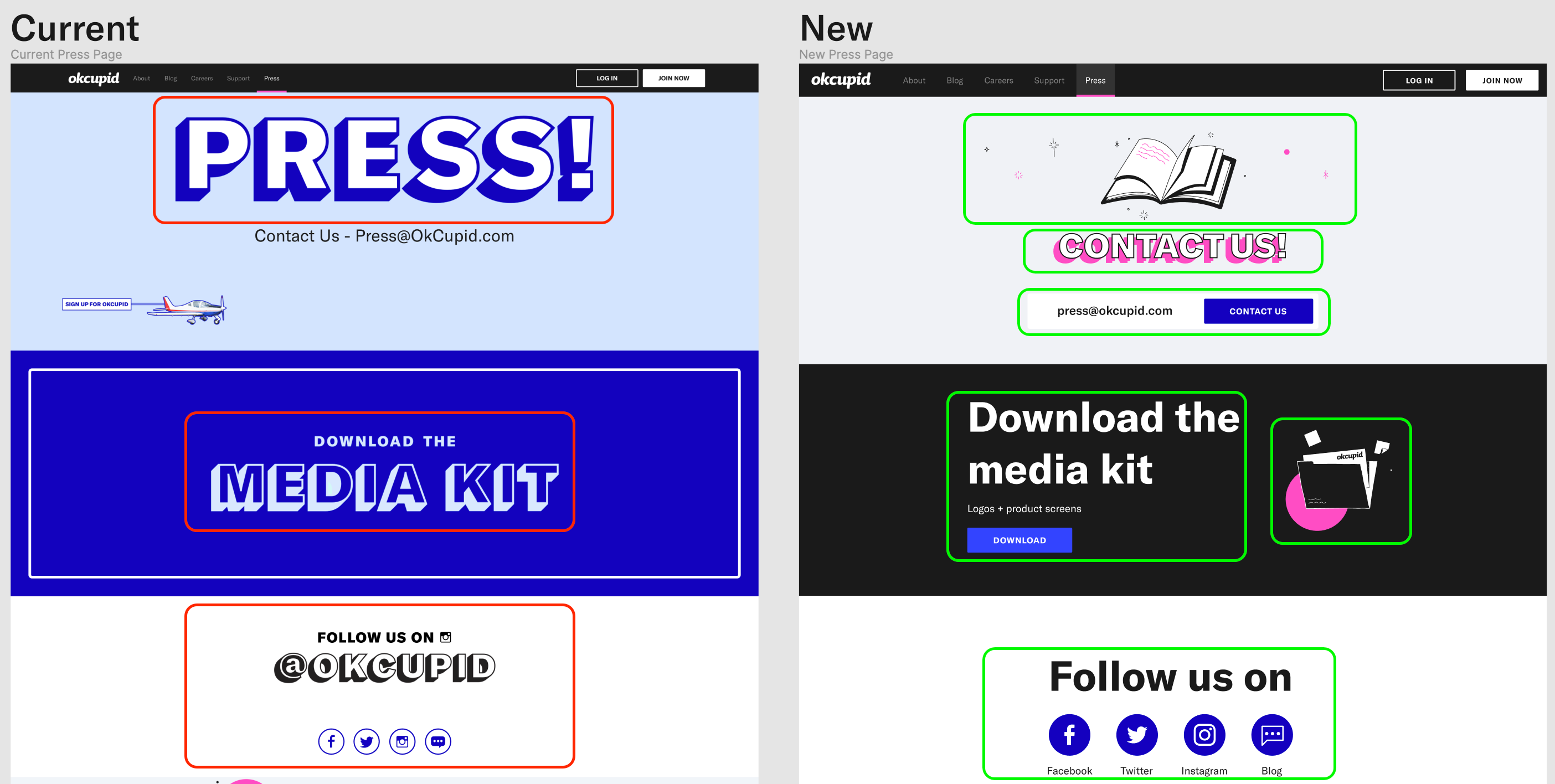

One interesting point of discussion would be OkCupid’s current attitude toward localizing assets. Perhaps your application uses a large amount of static images. Often, it’s common to find text baked directly into these images, which allows for us developers to not have to worry about the styling of these assets, we just drop them in and they look correct. However, it now means that these assets too need to be localized, and if you plan to scale to even a few (let alone tens) of languages, the tedium of creating / exporting / importing these assets based on specific locale will increase linearly for designers and developers. It’s for this reason, we decided to try removing embedded language in our assets, and using more neutral assets that could work in a variety of languages and cultures. Here’s a dead-simple example for illustrating this:

Text-based assets vs. illustration-based assets and native text

Text-based assets vs. illustration-based assets and native text

The elements outlined in red on the left are actually image assets, text and all, loaded from the CDN. In green on the right, the images have been separated from the text, so that text content and image assets can be rendered independently from within React / CSS without a need for deploying numerous images to the CDN for each language.

We also created some cool custom text rendering classes to handle our styles in a localizble manner. Check out the post on that here.

Is it really a constant?§

I’d like to wrap up the more specific technical considerations by providing a small anecdote about an issue that I ran into, and the philosophical / architectural point it brought up in my mind about my code. At some point, I had a message prepped for translation and couldn’t figure out why this message was not coming back properly translated.

Well, it eventually turned out to be that the translation was applied when the file was imported, because it was defined as a constant, and so it was never re-evaluated after it’s initial evaluation (and in this case, it did not yet have the most up-to-date data to perform the correct evaluation).

It’s common place for us to colocate pieces of our codebase, and often that involves taking primitive data types like strings and declaring them once as constants and reusing them throughout files and modules in a codebase. However, when you are using something like React Providers and Context to apply a locale across components or an app, your “constants” are now subject to change based on the state of the application. Are these really constant anymore? It’s certainly a small difference, but highlights the fact that something as trivial as declaring constants need to be reconsidered under the light of internationalization.

It’s also a good little exercise for writing software! Deconstructing your work and asking yourself whether or not what you’re doing makes sense contextually is a hard skill to master, but certainly valuable in avoiding situations like this (and for just building software in general).

Check out part 4 of this series here.